Is ESG the future of active management?

Fund managers are taking advantage of soaring interest in sustainable investing

Environmental, social and governance principles have become such a dominant force in investor sentiment in recent years, and particularly over the past 12 months, that there seems to be little else that fund managers are interested in.

Such is the interest among investors, wanting to know that their money is being put to good use, that many active funds have been launched, which to varying degrees, claim to be following ESG sentiments.

But, even if the approach, where the managers have to closely scrutinise exactly what their investments are doing, suits the active philosophy, there is very little standardisation over what ESG means.

On top of this, the passive sector is getting in on the action, and many passive ESG funds are being launched. The question is: is the fund management industry undergoing a long-term structural shift, as social and corporate values change?

Advisers expect to increase their ESG exposure

Around 60 per cent of advisers anticipate increasing their exposure to sustainable investment funds this year, according to the latest FTAdviser poll.

The poll, which was conducted via the FTAdviser Twitter account, found that 60 per cent of respondents intend to increase their investments in funds that have a clear focus on issues around clients' interest in companies with a focus on sustainable investments.

FTAdviser previously reported that inflows into such funds quadrupled in 2020, even after having reached the level of £124m a week in 2019.

Despite those inflows, responsible investment funds still make up only about 3 per cent of the total market in the UK.

Providers continue to launch new products with the aim of capturing some of the flows going to this trend, with Liontrust the latest to announce its intention to bring a sustainable-investment-focused investment trust to market.

Such funds have gained considerable prominence over the past year as a result of a strong period of performance in the pandemic, while new regulations require advisers to ask ESG questions as part of the suitability questionnaire, and are helping to drive demand, while greater clarity has also been provided at the European level as to what constitutes an ESG fund.

ESG is providing a way forward for the active management industry

It is no secret that the active management industry has been on the backfoot.

In terms of performance, many fund managers struggle to consistently beat the market.

The 2020 year end Spiva scorecard, published by S&P Dow Jones Indices, found that fewer than one in 10 sterling-denominated US equity funds outperformed the S&P 500 in the decade to the end of last year.

While the US market is notoriously difficult to beat, the results are not especially encouraging elsewhere. Most global, emerging market and European funds also struggled.

In the case of the best performing group, UK small cap equity, less than 40 per cent of funds outperformed.

As the chart below shows, the results have looked more encouraging in the shorter term, especially when it comes to UK and European equity portfolios.

But whether because of performance issues, a growing awareness of cost or other reasons, investors have steadily migrated to passive funds in the past decade.

Investment Association figures show that trackers made up 18 per cent of the assets held in open-ended funds by UK investors at the end of January this year – a huge leap from their 6.9 per cent market share at the end of 2011.

These figures do not even account for the significant volumes of money in exchange-traded funds.

While uncertain times are often seen as a chance for stock-pickers to shine, we are yet to see that the pandemic has done anything to halt the shift to passive.

Suggestions of passives' market share having 'peaked' in 2020 are also yet to prove obviously correct. Calastone, another organisation tracking fund flows, noted that when traditional active equity funds suffered heavy outflows in January this year, index funds continued to pull in money. “Despite the sharp reversal of investor sentiment, [index funds] enjoyed inflows of £485m in January,” the business noted. This was in line with the monthly average of recent years, if lower than in some previous months.

But a more promising future may be emerging for the active management industry. While passives might continue to either snatch market share or at least maintain their presence, another source of growth appears better suited to active.

The same Calastone data, covering January’s fund flows, points to this. While the research paints a picture of passive funds prospering over 'traditional' active products, active ESG funds soaked up investor assets.

ESG equity funds enjoyed their third best monthly inflows in January according to Calastone, marking the continuation of a trend that appeared to finally take on momentum last year.

In one form or other, ESG looks to define the future shape of the industry. But this will pose its own risks and challenges.

Equally, there is no guarantee that active ESG will escape the passive threat. Importantly, any form of ESG exposure will require a significant level of knowledge and due diligence from intermediaries.

ESG: an active manager’s game

Andrew Bailey pointed to both these developments a few years ago. In a 2018 talk to the Investment Association’s Culture Conference, the then FCA boss suggested that the rise of passive and ESG, respectively, would be two defining trends for the investment industry.

Yet, he hinted that ESG would be better suited to an active format.

“A longer-term shift towards passive investing goes alongside a desire for more ethical and socially responsible investing and a desire to encourage longer-term patient capital,” he said.

“Of course, these two developments can co-exist. Indeed, I would go so far as to say that they will, and that in doing so there will be some re-clarification of the meaning of active management.” He added that passive could co-exist with “a world where investors also want to express a preference which embodies their values and longer-term goals, with ethical objectives, for instance”.

A longer-term shift towards passive investing goes alongside a desire for more ethical and socially responsible investing

The idea of active as a natural home for ESG makes sense, given the need to carefully choose suitable investments. Active can also cater to the subjective nature of definitions such as 'ethical', to an extent.

Well-known ESG fund managers, including those on the WHEB Sustainability fund and Liontrust’s Sustainable Future range, will often tend to break their portfolios down by different investment themes.

Investors can, to some degree, assess these and decide whether a fund’s approach is in line with their beliefs.

Investors also have a choice of more targeted funds if they wish. Morningstar data found that while 372 'broad ESG' funds launched in Europe last year, 64 environmental funds also arrived. Some 25 social impact funds launched, with 24 new funds focused on other themes.

Some investors, of course, will have idiosyncratic views on what is ethical, sustainable, or in keeping with other criteria of importance to them. They may be best suited to an individual approach, such as a bespoke portfolio run by a wealth manager.

Inevitable complications

With asset managers flocking to enter the ESG space, several complications have emerged, both for product providers and their customers.

Firstly, there is the question of what is authentically ESG, an issue that challenges many parts of the investment industry. Companies, or other organisations, may attempt to brand themselves as ethically or environmentally minded in a bid to attract equity or bond investors.

Funds may therefore end up investing with companies or other organisations that actually fall short on the ESG front. Controversially, ethical funds run by the likes of Aberdeen Standard Investments and Premier Miton Investment were found to have positions in Boohoo when the fast-fashion name was hit by allegations relating to working practices in mid-2020.

Even investments widely held by ESG funds with good reason can run into trouble: Kingspan, an insulation specialist previously held by various ESG managers, has become ensnared in the Grenfell Tower fire scandal, for example.

Other holdings will prove highly divisive: the green credentials of Tesla, a big holding for Baillie Gifford’s Positive Change fund, came into question earlier this year when the company invested in bitcoin. The cryptocurrency is controversial in part for how much energy it consumes.

Likewise, some funds may have taken on ESG as a marketing label without implementing the correct processes. Morningstar’s assessment of 2020’s ESG trends found that of the 253 funds that “repurposed” as sustainable in Europe last year, some 87 per cent had simply done so by rebranding their portfolio. Investors may therefore wish to be careful about fund providers that have only recently taken an interest in ESG.

What does ESG even entail?

What’s more, interpretations of ESG are evolving. Some funds will avoid 'bad' stocks or bonds in controversial areas, from oil and gas to tobacco and weapons. Others, such as WHEB Sustainability, will only back companies that are making a direct positive contribution to the cause they favour.

And yet another form of ESG, in which fund managers hold 'bad' companies but engage with them to advocate change, is gaining prominence. This could be especially important in regions such as the emerging markets, where stopgap solutions may be required. Renewables may not immediately be in place to enable a straightforward shift from 'dirty' to 'clean' energy sources in this part of the world, for example.

It is therefore worth noting a manager’s approach and how that fits in with different philosophies. Funds without an explicit ESG remit can also fit into the picture: even value funds, which often focus on industries such as oil and gas, may end up backing 'bad' names which stand to benefit from an increased focus on sustainability.

Some managers will even defend certain holdings as having a greater ESG case than many assume.

Terry Smith used an interview with FTAdviser sister publication Investors’ Chronicle last year to argue that tobacco name Philip Morris had some merit on the ESG front because of its work to move smokers away from tobacco and towards alternative products.

Funds should not necessarily be dismissed for lacking an ESG label, as they may still follow some of the relevant processes anyway. The SDL UK Buffettology fund, a strong performer within its peer group, does use some ESG criteria when assessing potential holdings, though this tends not to be prominently discussed. That said, fund managers without an explicit ESG remit may feel less obliged to consistently focus on these metrics.

Passive push

Active funds in the ESG universe still face competition from passives. ESG trackers of different stripes have proliferated in the past year and have proved highly popular.

Morningstar notes that passive funds have seen their share of the European sustainable fund market increase “considerably”, from 10.3 per cent at the end of 2015 to 22.5 per cent five years later.

These passives come in various forms, from ESG versions of conventional market indices such as the S&P 500, to certain thematic funds. Notably, the iShares Global Clean Energy UCITS ETF took in billions last year, while also delivering phenomenal returns. It has made a 110 per cent sterling total return in the year to April 22 2021, notably outpacing conventional equity markets.

And yet problems also exist for ESG passives.

There are many 'light' ESG versions of existing indices that actually differ little from the parent market. Even stricter indices, such as MSCI’s SRI ranges, can have exposures that may not obviously fit the ESG theme. The MSCI UK IMI Low Carbon SRI Leaders Select index, for example, has a decent level of exposure to mining major Rio Tinto. The thematic funds can have their own issues, from having big stakes in small and mid-cap stocks, potentially causing liquidity issues, to having positions in more liquid names that seem only tangentially related to the theme.

Passives may, therefore, have their own problems in meeting an ESG investor’s criteria. The concept is likely to provide complications for both the active and passive industry, rather than just asset growth.

House View: Who’s making money from Covid-19 vaccines?

The distribution of Covid-19 vaccines is picking up pace globally. US President Joe Biden last month set a new target of 200m vaccination doses to be delivered in his first 100 days in office. The original target of 100 million was achieved before his sixtieth day in office.

The speed at which drugmakers were able to discover successful vaccines, undertake the necessary clinical trials, and then bring them to market in large volumes is testament to the ingenuity and innovation within the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries.

It shows what can be achieved when all participants - governments as well as companies - work together.

Limited boost to share prices

For investors, a key question is whether the vaccines will make money for the companies who invented them, and for their shareholders.

So far, the stellar success of the vaccines from a public health point of view hasn’t been reflected in the share price performance of the companies involved.

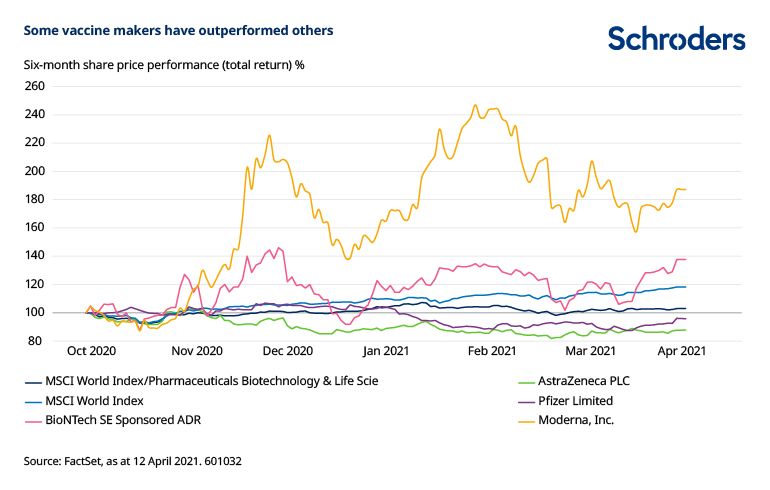

The chart below shows how Moderna enjoyed a share price spike alongside the announcement of its successful vaccine in November. BioNTech experienced a similar boost although the shares of its Covid vaccine partner Pfizer made smaller gains. Meanwhile, AstraZeneca shares have lost value over the last six months.

Supply problems and concerns over potential blood clots may have influenced these share prices moves, in addition to factors unrelated to the vaccines.

However, in part, some of the differences between the four companies’ share price performance may be down to the technology behind the vaccines.

BioNTech and Moderna are specialist biotechnology firms. The success of their vaccines vindicates the investment these firms have made in the novel mRNA technology. The value of this technology is shown by the speed at which the Covid vaccine candidates were produced, simply by using the genetic code of the virus. This mRNA technology will have many other applications aside from Covid.

One interpretation, therefore, is that the share price gains enjoyed by Moderna and BioNTech reflect the future potential of the mRNA technology, rather than the discovery of the Covid vaccines specifically.

Another consideration is that the companies behind the vaccines have the public good, rather than profits, at the forefront of their considerations.

Public before profits

As investors, we need to distinguish between the companies that have developed the vaccines, and those who are part of the vaccine production supply chain.

The developers – such as Pfizer, Moderna and AstraZeneca – have largely viewed this first phase of the vaccine drive as an act of public service.

It is part of the social contract such companies have: they want to show the value that an innovative biotechnology industry brings to society and to demonstrate how they can use their expertise to tackle a public health emergency like this.

AstraZeneca is the most obvious example as it is explicitly producing its vaccine on a not-for-profit basis. However, even Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna are not charging real commercial prices for their vaccines, and so are not making substantial profits in this first wave.

This is in contrast to the companies involved in the vaccine production process. They are participating on a much more commercial level and pricing their products – glass vials, etc – accordingly. They will therefore see greater financial benefit from this current ‘emergency’ phase of the vaccine roll-out.

Pfizer and BioNTech are charging c.$39 for their two-dose vaccine in the US. AstraZeneca is charging $4.30-$10 for its two-dose vaccine.

Vaccine developers have also agreed to provide doses to COVAX at a not-for-profit price. COVAX is a global initiative to ensure low income countries have access to Covid-19 vaccines. Pfizer and BioNTech, for example, have agreed to provide 40 million doses this year to COVAX while AstraZeneca is providing at least 170 million doses.

Next phase may bring greater rewards

However, the current cohort of available vaccines is unlikely to be the last. A number of Covid-19 variants have emerged and the efficacy of current vaccines needs to be tested against these.

Further variants may well emerge in future as a greater proportion of the world population is vaccinated, forcing the virus to mutate if it is to spread further. That could lead to a new phase in the production and distribution of vaccines.

Clinical trials are already starting on next generation Covid vaccines to tackle emerging variants.

Ultimately, we could see the Covid vaccines become part of the existing winter season vaccination programme. It may well be that a combined flu/Covid one-shot vaccine becomes available; companies are already working on that.

It is that next phase when the developers like Pfizer/BioNTech and AstraZeneca will start thinking about these vaccines in more commercial terms, just as the producers of flu vaccines do. That will then provide more enduring, long-term value to these companies. And the companies in the supply chain will continue to benefit too, along with the developers.

John Bowler is a fund manager, global healthcare, at Schroders

Any company references are for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation to buy and/or sell, or an opinion as to the value of that company’s shares.

The article is not intended to provide, and should not be relied on, for investment advice or research.